1924: Hilltoppers’ Star Saved in Swimming Pool

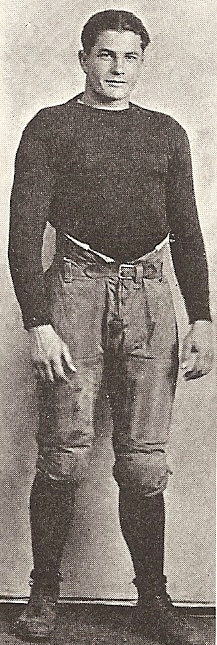

San Diego High avoided a tragic event when star sophomore fullback Bert Ritchey almost drowned before the Hilltoppers’ “bowl game” at Phoenix Union.

After a 12-hour ride on a special San Diego & Arizona railroad car and arriving Friday morning, the Cavemen worked out at Phoenix’s Riverside Park late Friday afternoon. That evening many in the squad took advantage of a nearby swimming pool.

Ritchey got into trouble but was not noticed until Werner Petersen saw his teammate lying at the bottom of the pool.

Petersen quickly dived, embraced Ritchey, and got his teammate to the surface, according to the report in The San Diego Union.

Ritchey was shaken but okay after a few minutes.

Coach John Perry declared the youngster out of the game, but Ritchey played about 10 minutes the next day, according to various reports, and scored a touchdown in the 14-13 victory.

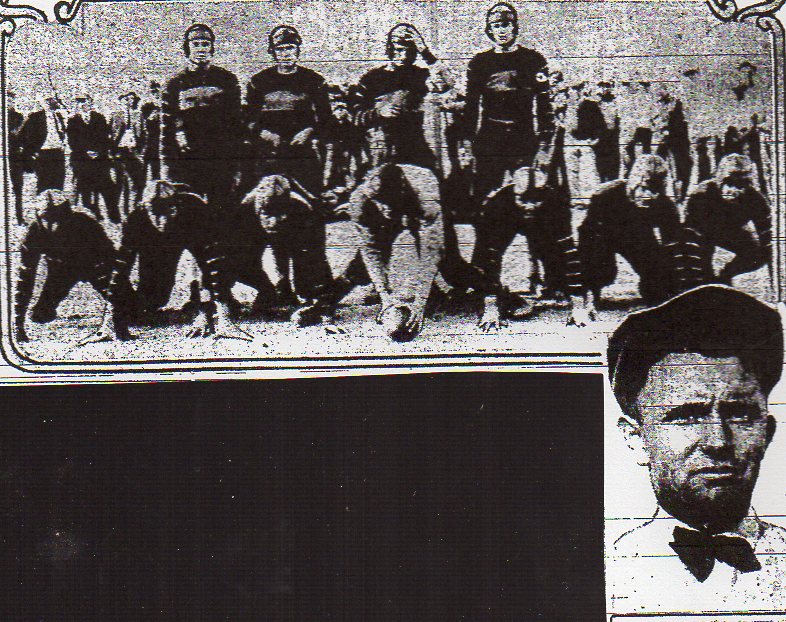

Perry had scheduled the game late in the season as a reward for the team after the Hilltoppers had clinched the Coast League championship.

Following the Saturday afternoon contest, the Hilltoppers boarded a railroad car for another 12-hour trip back to San Diego, arriving Sunday morning.

RITCHEY’S NAME RESONATED

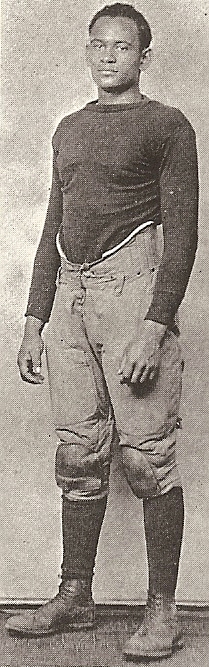

Big Ritchey, a 180-pounder, was born in Kansas and moved to San Diego at a young age in 1909, when his family lived downtown at the corner of Front and F streets. His was one of the earlier African-American families to settle here.

Bert’s younger brother, Johnny, was the first black player in baseball’s Pacific Coast League when he joined the San Diego Padres in 1948.

Ted Ritchey, the star of San Diego High’s 1947 Southern California finalist, was a nephew of Bert, who also had athletic brothers Alfred and Earl.

SOUR ORANGES

According to The San Diego Union’s Alan McGrew, the Cavemen wasted five scoring opportunities in their 0-0 tie at Orange.

“The game might be a moral victory for Orange,” wrote McGrew. “Their ability to hold San Diego at times appeared uncanny.”

McGrew, who had been particularly critical of Perry in 1923, took a shot. “San Diego either lacked good plays or good judgment in their many attempts to score.”

Orange scored more than a moral victory in the quarterfinals of the playoffs. The Panthers took a 17-0 lead and returned intercepted passes 35 and 60 yards for touchdowns in a 29-20 victory over the Hilltoppers.

Orange scored three touchdowns on intercepted passes, a safety, three PAT, and two field goals, one from the 40-yard line.

The Panthers’ first touchdown came on a 95-yard intercepted pass return by Wuelff.

According to historian Don King’s Caver Conquest, San Diego stunningly outgained Orange, 559 yards to 98, and held a 33-1 advantage in first downs.

Who was keeping the stats?

PERRY WANTS TO PEEL ORANGE

The yardage anomaly was reason enough for coach John Perry to seek a third game. He challenged Orange to a Christmas Day showdown in San Diego.

“I am confident that our team is better than Orange,” said Perry. “They did not score on their own plays but on our fumbles.”

The challenge was in play only if Orange did not win the Southern California championship. Orange wasn’t interested after playing five postseason contests and being eliminated in the semifinals

COMPLEX PLAYOFFS

One had to follow closely to understand the postseason.

Orange defeated Redlands, 39-0, in the first round.

Orange defeated San Diego in the second round.

San Diego had a first-round bye and Sweetwater had first-round and second-round byes (not an unusual procedure for that era since travel and who was available came into play).

Orange defeated Sweetwater, 14-0, the following week in the quarterfinals.

Glendale and Compton deadlocked, 0-0, in the semifinals and, by rule, played again the following week, Glendale winning, 7-0.

The Dynamiters then defeated Compton, 24-0, for the championship as star lineman Marion Morrison played his final game before moving on to USC and later was successful in the movies under the name of John Wayne.

CAVEMEN GRIND

Having first played Santa Ana in 1905, the Saints were the Hillltoppers’ oldest intersectional rival and this year’s game, a physical, 13-0 San Diego victory, showed how much coach John Perry team liked to run the ball.

Individual game statistics for high school games were rarely published, but someone kept a record in this game.

Bert Ritchey gained 76 yards in 25 carries and scored 1 touchdown. Phil Winnek had 50 yards in 12 attempts and scored once. In all, the Hilltoppers rushed 58 times for 171 yards.

MONEY TIGHT

San Diego B coach Gerald (Tex) Oliver greeted 60 candidates, all reportedly fewer than 140 pounds and averaging 132 (Sweetwater had 62 B prospects, with about 30 that weighed no more than 110) and Oliver was hard pressed to outfit all.

The San Diego board of education denied an appropriation for the Hilltoppers’ B squad, so Oliver planned benefits.

The “Infants,” as Oliver’s club was known, charged 15 cents for a game with La Jolla.

‘BEES’ VITAL

Usually fast and experienced, most B players had participated in junior high or interclass competition.

With eligibility based on “exponents”–height, weight, and age–B teams, similar to junior varsity squads, were an integral part of Southern California football programs for many years.

Many players would start with the B team but advance to the varsity and return to the B’s in the same season.

The San Diego varsity generally practiced at 2 p.m. in City Stadium, followed by the Bees at 4.

IT’S ABOUT THE GREEN

Sweetwater’s student executive committee voted for the Red Devils to give up a possible home-field advantage and play San Diego in the City Stadium.

The committee rubber-stamped the request of athletic manager Cheeney Moe and head coach Herb Hoskins, who wanted the gate receipts from a larger turnout in the stadium to go to improving the school’s football facilities.

MISPLACED CONFIDENCE?

Hoskins, whose teams were in the Southern California playoffs four out of five seasons in the 1920s, didn’t flinch when asked his team’s chances against San Diego in the season opener.

Writer Alan McGrew of The San Diego Union asserted that the Sweeties had lately “taken some of San Diego’s thunder”.

“We’ll win,” said Hoskins. “We never figure on losing when we enter a game. I am confident we’ll win.”

The Cavemen defeated the Red Devils, 33-0, as Bert Ritchey made his debut with four touchdowns.

COLLEGE BLOWUP’S FALLOUT

Stanford and California announced they were suspending relations with the University of Southern California at the end of the season.

Things had soured between the Pacific Coast powerhouses, with the Northern schools, original conference members since 1915, accusing the Trojans, who joined in 1922, of paying players and not enforcing admittedly vague conference academic standards.

USC promptly announced it was a canceling a home game that week with Stanford, saying that the Northern schools had challenged USC’s “honor”, had a “anti-Southern California feeling” and that the Trojans had always played by the rules.

The USC action affected that week’s San Diego-Long Beach Poly battle for the Coast League title.

Originally scheduled Saturday, Poly boss Harry Moore announced a switch to Friday, not wanting to go against USC-Stanford.

When USC bailed on Stanford, Moore switched again, back to Saturday, saying that his school would “lose too much money” and a probable big San Diego crowd by playing on Friday.

San Diego clinched a tie for the Coast League championship with a 6-3 victory over Poly in a taut defensive struggle. The Hilltoppers’ Rocky Kemp kept the Jackrabbits backing up with booming punts, one traveling 80 yards.

CAVEMEN ON CARPET

Northern schools in the Coast League also were angry with one of their brethren.

San Diego High vice principal Edgar Anderson was called to Los Angeles for a meeting in which the Hilltoppers were forced to defend themselves against possible expulsion.

Fullerton’s principal charged the Hilltoppers with “rough tactics” in San Diego’s 33-7 victory weeks before.

One Indians player “even had a black eye”, said the school administrator.

Fullerton coach Shorty Smith complained to officials at the end of the game that the Cavemen were “holding” and “coached to play dirty.”

THEY CAN’T HEAR WHISTLE

Pasadena also pointed out that San Diego was penalized twice for roughing.

The Union’s McGrew dismissed the charge by noting that the locals only “kept on playing after the whistle”, which apparently was okay with the writer.

The meaningless vote, which needed the CIF’s approval, was 3-2, with Pasadena backing Fullerton.

Whittier, Santa Ana and Long Beach Poly sided with their Border City rival.

INELIGIBLE?

Fullerton also claimed that Hilltopper Alden Johnson, son of the San Diego City Schools superintendent, was not on the eligibility list when the teams met.

San Diego stated that Johnson indeed was eligible but was on the “Seconds” squad and didn’t play.

Edgar Anderson then stuck it to Fullerton by producing an eligibility document sent by Fullerton during the previous track season.

The Orange County school’s list had only a scarce number of athletes cited, not nearly enough for a track meet. Instead of being on the Coast League’s official form, the information “was on a piece of scratch paper,” said the San Diego official.

CIF NOT HAPPY

The Hillers did not have clean hands.

“San Diego High was in hot water during this time period, because of not following CIF rules. There were delays in making reports (forwarding game receipts, etc) ,” said CIF Southern Section historian John Dahlem.

Similar complaints of travel were voiced many times over the years.

TROUBLE NEAR THE OCEAN

Army-Navy also drew the wrath of the Southern Section.

The Cadets’ starting backfield and three linemen were declared ineligible thirty minutes before kickoff against El Centro Central.

Thirty players in all were banished from football, according to coach Ed Tarr.

Alan McGrew wrote that “most of the ineligibility was caused by students transferring from other schools after being out a semester.”

McGrew was emotional.

The scribe declared that “the murder of Caesar was nothing compared to the ‘crime’ the Southern California Interscholastic Federation, boss of prep sports in this section, has committed.”

Minutes from a Southern Section executive committee meeting 10 days before did not shed much light, only that games played by Army-Navy “are not to count towards a championship in any way.”

The CIF was uneasy about the Pacific Beach military boarding school, whose perceived unfair housing advantage raised questions of residence and eligibility.

TARR REGROUPS

The Army-Navy coach announced that he would have to dismantle the “Seconds” team and that he was debating whether to field an “Ineligible” squad.

Tarr thought his ineligibles could meet the San Diego Lightning squad.

The Lightning also was comprised of ineligible players and was coached by Rupert Costo, a 200-pound Native American lineman who was expected to be a starter on the Hilltoppers’ varsity.

Costo had gotten the rubber key from school officials after he had exhausted his eligibility when it was discovered that Costo had attended “several other high schools.”

SIGNS OF THE TIMES

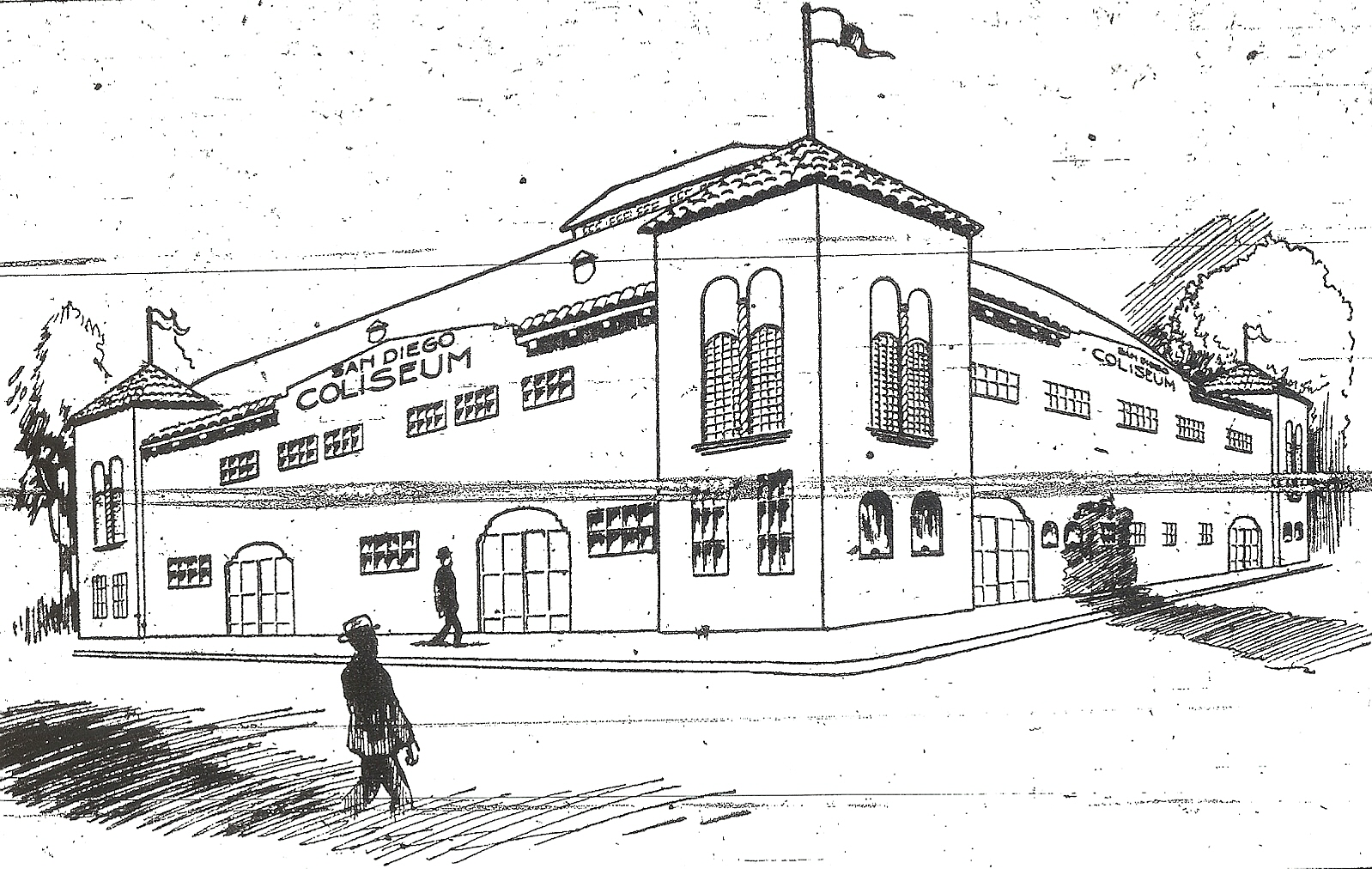

The new Coliseum Athletic Club was being constructed at 15th and E Streets. “Every possible modern convenience” was to be included in the 4,500-seat stucco and tile structure.

TASTY

Carlsbad celebrated its second annual “Avocado Days”. Some 2,000 guests enjoyed Avocado soup, Avocado sandwiches, and Avocado ice cream.

A dance concluded the event, at which a local Avocado honcho said the fruit had made the North Coast of San Diego County famous.

WILSON JUNIOR HIGH ON DECK

Low bid of $247,000 was submitted by contractor William C. Reed for construction of Woodrow Wilson Memorial Junior High at 37th Street and El Cajon Blvd., in East San Diego.

Wilson would open in 1926 and be the primary feeder for a high school that was to be built later in the decade. That school would be named after future President Herbert Hoover.

PARK THE CARS HERE

The last quarter of Coronado’s 38-12 victory at Army-Navy was played with the aid of automobile lights.

Many scoring plays and penalties meant a longer game and late October’s dwindling sunlight contributed to the need for artificial illumination.

STEPPING STONE

Pay dues at Memorial or Roosevelt, the city’s two junior highs, which opened in 1922 and ’24, respectively, and be promoted to the high school.

Future San Diego coaches Dewey (Mike) Morrow and George Hobbs were on the Memorial staff.

FOOTBALL AT PARKER

Francis Parker in Mission Hills announced Sept. 4 it would field a high school football team this year, under the guidance of Lloyd Prante, former Nebraska player.

The school, which opened in Mission Hills in 1911, would move to Linda Vista in the late 1960s and begin playing football again in 1969.

LARGER LOOP

The County (Southern) League, inclusive of all schools other than San Diego High, entered its eighth season of operation with a double, round-robin schedule and welcomed newcomer La Jolla Junior-Senior High.

Other football-playing members were Grossmont, Sweetwater, Escondido, and Coronado. Point Loma would open and join the league in 1926.

FOOTHILLERS HEAD FOR HILLS

Twenty-one Grossmont players and coach Ladimir (Jack) Mashin engaged in a one-week camp at Pine Hills YMCA (later known as Camp Marston) in Julian.

“Most of the boys have been on ranches all summer with little time for recreation,” explained principal Carl Birdsall.

The group was accompanied by a chef. Goal posts were added to the athletic field, and a swimming pool was available.

TRUE GRID

San Diego had one player on the all-Southern California team, blocking back Russ Saunders…Glenn Rozelle, the uncle of future NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle, also was a first-team choice, from Compton…San Diego players didn’t practice on the first day of school, instead watching a slow-motion film on fundamentals, instructed by USC coach Gus Henderson and Notre Dame boss Knute Rockne…Grossmont defeated Brawley, 6-0, in the first ever game between San Diego and Imperial County clubs…the Pasadena Star newspaper ordered a phone line for the City Stadium press box so its correspondent could provide a running, play-by-play of the Bulldogs’ game against San Diego…San Diego and the Pomona College freshmen almost evenly split 25 punts and Pomona missed four field goals…”Blackboard” practice was a precursor to modern-day game film…coaches diagrammed plays on a chalkboard and tested the players…