Their story could have been inspiration for “The Grapes of Wrath,” because Bill Nettles and younger twin Wayne lived the life of John Steinbeck’s poor and displaced.

Teenagers, age 16, caught in the poverty of Oklahoma’s depression-era Dust Bowl, sought a way out.

With the spirit and optimism of youth, the youngsters decided to make their way West.

The twins hopped a passing freight train near Claremore, Okla., when their mom, the widow Pearl, wasn’t looking, according to John Nettles, Bill’s oldest son.

Armed with a roll of salami and a long loaf of bread, Bill and Wayne rode the rails that followed the route of the highway U.S. 66.

Trouble loomed when the twins became separated during a stop near Albuquerque, New Mexico.

“Wayne was out looking for around for food when he was discovered by one of the bulls,” said John Nettles.

The bulls were the feared railroad security guards.

Wayne was forced to return home, but a couple weeks later he caught another freight and soon was reunited with his brother. Bill had reached relatives in Flinn Springs

A PLACE TO STAY

The Nettles’ cousins, Ernie and Joe, lived in Flinn Springs. a tiny, unincorporated community east of El Cajon and west of Alpine.

That’s where the boys found a home and a promising future.

They soon would enter high school. The closest was Grossmont, about 11 miles away.

It was August, 1932.

The Foothillers of coach Jack Mashin were enjoying the most successful era in school history, posting a record of 35-5-2 from 1931-35 that included a streak of 23 wins and one tie.

(“We have a wide-awake club, a bunch of boys who take advantage of every break,” Mashin explained of the Foothillers’ success).

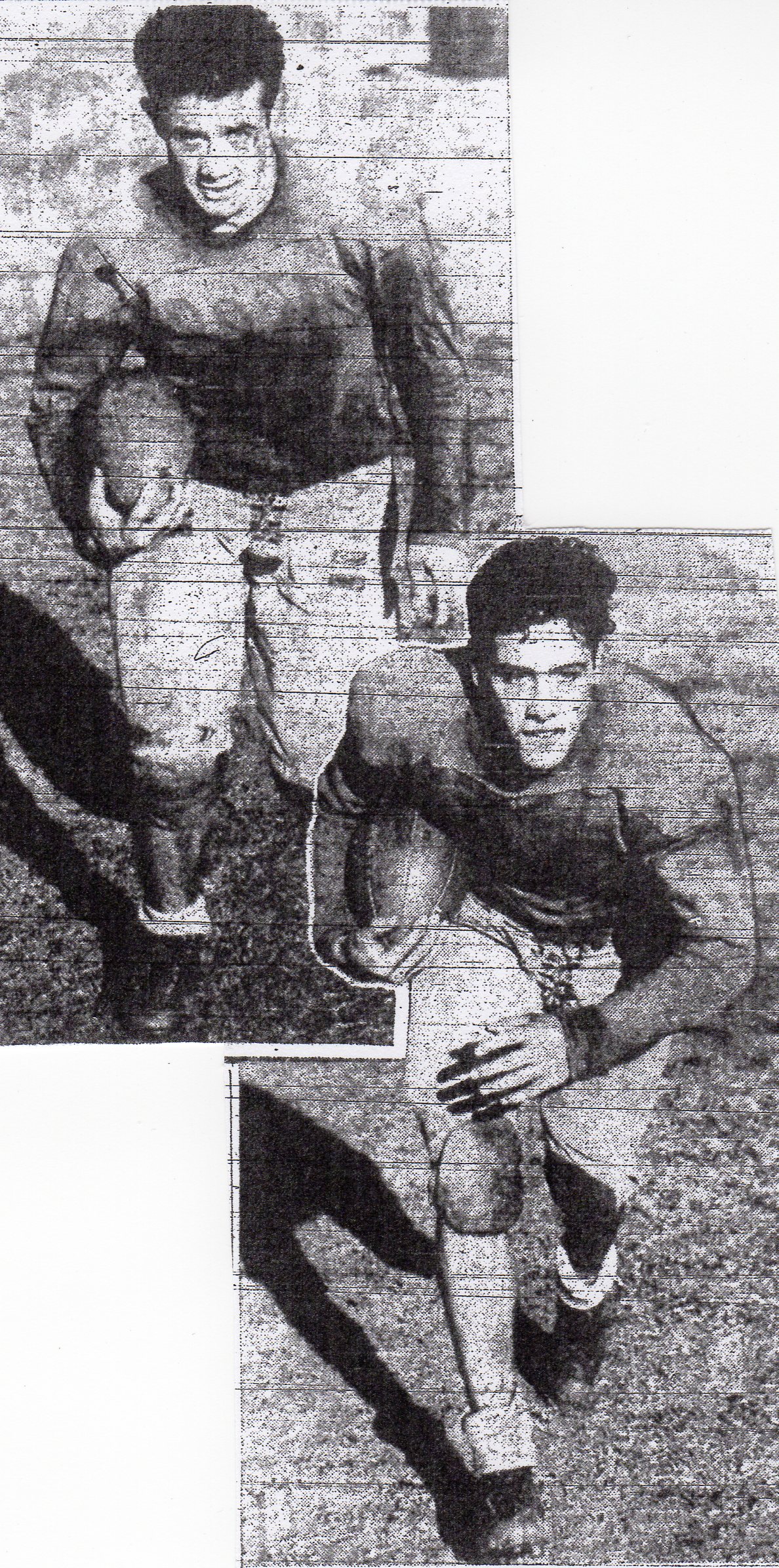

Bill Nettles played end and Wayne was the center.

Mashin’s squad was assured its second straight 9-0 season when Bill out-jumped three Coronado defenders to catch Ben Reynolds’ pass for a touchdown on fourth down and 18 to give Grossmont a 7-0 victory.

The win wrapped up another Metropolitan League championship and Bill Nettles was one of the leading scorers in the County with 8 touchdowns and one PAT for 49 points.

Pearl Nettles’ sons had made a name for themselves and then moved on to Glendale Junior College. They closed out their collegiate careers in 1938 as members of San Diego State’s Southern California Conference champion.

TRUE STORY

The brothers bore such striking resemblance to each other that Bill once mistook himself for Wayne.

For a game at Fresno State, Bill was part of the first group of players traveling. Wayne was to come with another group the next day.

When Bill entered his hotel room, he faced a full-length mirror. “What are you doing here, Wayne?” I thought you were coming up tomorrow,” said a confused Bill as Bill looked at Bill.

NETTLES EVERYWHERE

It was their offspring that forged a family legacy.

Bill’s son, John, was an all-San Diego Section end at St. Augustine in 1961.

John’s younger brother, Tom, was a basketball star at Hoover, earned a letter as a javelin thrower at San Diego City College, and caught 68 passes for the 1968 San Diego State football team.

Tom Nettles was drafted by the NFL Kansas City Chiefs and played in the 1975 U.S. Open golf championship.

Wayne Nettles’ son, Graig, was an all-Southern California selection in basketball at San Diego High and is best known for a 22-season major league baseball career, including 11 with the New York Yankees and three with the San Diego Padres.

Graig was one of the key players in the Padres’ drive to their first National League pennant in 1984.

Jim Nettles, Graig’s younger brother, played basketball and baseball at Crawford High and six seasons in major league baseball.

AMBLIN’ AMBY

San Diego’s Ambrose Schindler, the leading scorer among major schools with 15 touchdowns and 90 points, was the Southern California player of the year.

The only other area athlete from a major school to match Schindler’s football honor was San Diego’s Charlie Powell in 1950.

Schindler broke long runs and ran with toughness.

No records for total yardage exist, but Schindler ran inside and outside. In a 13-7 victory over visiting Pomona the product of San Diego’s Mission Hills community and Roosevelt Junior High rushed for 301 yards in 28 carries.

POLY RULES AGAIN

The Cavers were 16-3-2 in Schindler’s last two seasons but couldn’t get past Long Beach Poly this year, losing 20-13, on the road, finishing second in the Coast League, and out of the playoffs.

Years later Schindler, who went on to star at USC, returned to the scene of his high school glory.

Schindler annually worked San Diego Chargers games in Balboa Stadium as a member of the American Football League officiating staff.

ADAMS RETURNS TO TROY

Nelson Fisher of The San Diego Sun broke the news that Hilltoppers coach Hobbs Adams was leaving to accept a line coach position at USC, his alma mater.

Adams had just been elected head of the San Diego County Football Officials’ Association at that group’s season-ending awards banquet at Plata Real in the U.S. Grant Hotel.

Adams told Fisher that “I haven’t heard anything official yet, but I’ve always had a somewhat hidden desire to get back there with (USC coach Howard) Jones.”

Adams was 41-11-3 in six seasons with the Cavemen and took the 1933 team to the Southern California finals.

The former Hilltoppers player and San Diego native was 2-4 against arch-rival Long Beach Poly, all of the losses close and all almost impossible to swallow.

BRODERICK GETS POST

Early speculation on Adams’s successor centered around Bert Heiser, coach at Chaffey Junior College in Ontario, and Leo Callan, a Hilltoppers alum who was head coach at the University of Idaho and a former USC all-America.

San Diego principal John Aseltine stayed at home, elevating Glenn Broderick, who was on staff and had served as head track coach and Class B football coach.

AMBY TO NAVY?

An announcement by Hobbs Adams late in the season revealed that Schindler had been accepted at the Naval Academy and would enroll after his midterm graduation in February, 1935.

Schindler would play for coach Tom Hamilton, a former Navy all-America who had connections in San Diego and had just finished his first year as the Midshipmen’s coach with an 8-1 record.

Schindler never made it to Navy. He changed his mind. Perhaps it was coincidental with Adams’ change of address, but Schindler landed at USC.

It was a good move for Adams and Schindler and for Howard Jones. Schindler played on USC’s Rose Bowl-winning squads in 1939 and ’40 and was most-valuable player in the 1940 Chicago All-Star game against the NFL champion Green Bay Packers.

Schindler was a 13th-round selection of the Packers and the 119th player in the 1940 draft but opted for coaching on the high school and junior college levels.

RISING IN THE EAST

Hoover was in its fifth year and ambitious.

The East San Diego school had dropped out of the City Prep League after the 1932 season and, as an independent, sought a stronger schedule and more recognition.

A game with San Diego High, first earned in 1933, was only part of the plan.

The Cardinals celebrated the opening of their turfed, 4,000-seat stadium this year. With financial help from the school faculty (encouraged/pushed by principal Floyd Johnson), Hoover was the first area high school to also have lights.

La Jolla and Coronado followed Hoover with lights later in the decade. Balboa Stadium wouldn’t become illuminated until 1939. Navy Field, to become known as Sports Field, had temporary lights in 1930 but was essentially void of seating.

FUTURE COACH SIDELINED

Roy Engle, a junior who would become one of the Cardinals’ best players and later a legendary coach, was sidelined for six weeks after he sustained a broken collar bone in the Reds-versus-Whites, preseason, intrasquad scrimmage witnessed by virtually the entire student body, approximately 1,300.

BITING OFF A BIG CHUNK

Cardinals coach John Perry continued to upgrade his team’s schedule, but a road game at Santa Barbara was a disaster, after the Cardinals had shut out their first five opponents.

A 41-7 loss, in which the Cardinals scored only on a blocked kick recovered in the end zone and were outgained, 461 yards to 117, began with a daunting logistical challenge.

The game at Santa Barbara’s Peabody Stadium was about 210 miles from the Hoover campus, where 25 players plus supernumeraries caravanned in automobiles on Sunday evening.

The players spent the night at the YMCA in downtown Los Angeles and were joined by coaches John Perry and Bill Bailey the following morning for the 70-mile ride to the stadium on the Dons’ campus.

TEAMS CLOSE?

The Cardinals arrived a couple hours before the Armistice Day kickoff for a matchup that San Diego sportswriters had determined as being “pretty even.”

According to “The Punter,” a nom de plume used by the prep writer of The San Diego Sun, “It was all Biff McLaughlin’s fault.”

McLaughlin passed for two touchdowns and ran for one as the Dons took a 21-0 lead in the game’s first seven minutes.

According to The Punter, McLaughlin was going to quit school the next year to sign a Pacific Coast League baseball contract.

The Santa “Barbarians” were made up of players “19 to 20 years old and none of them weigh less than 190 pounds,” wrote The Punter.

Hoover’s day was not over. The team would arrive back on campus late in the evening, so the players could attend classes Tuesday morning.

ANOTHER STRANGE TWIST

Hoover had another tough opponent scheduled four nights later against visiting Los Angeles Loyola. The loss to Santa Barbara, leaving the Redbirds with a 5-1 record, had apparently eliminated them from playoff consideration.

A rainy week in San Diego prompted a weird response from Loyola officials. They canceled the game, 24 hours before kickoff, allegedly declaring they did not want to soil their new uniforms on a muddy field.

Speculation was that the Cubs were locks to make the playoffs and didn’t want to risk a possible road loss.

Floyd Johnson was miffed.

The Hoover principal had a sympathetic ear from CIF bossman Seth Van Patten, who ordered Loyola to play the game the following week.

Oh, and while we’re at it, we’ll make this a first-round playoff, said Van Patten.

The Cardinals were assuaged. They got the game and the promise of a solid financial return and they also were in the postseason.

The Cubs spoiled the evening, defeating Hoover, 14-7.

The Cardinals dropped a 14-0 decision to San Diego the following week in the second annual Elks Charity game and flattened out to a final, 5-3 record as San Diego rushed for 283 yards to 125 and Schindler scored on a 52-yard run.

But Hoover was getting closer to the Hilltoppers and it looked with confidence to the 1935 season.

STRANGER THAN FICTION

Hoover scored all its points in the first eight minutes of a 15-0 win over Point Loma. The Cardinals blocked two punts in the first quarter, Bob Summers covering one of blocks in the end zone for an apparent third touchdown.

The jubilant Summers hurried to the Hoover bench, but the whistle had not blown. Point Loma covered the ball for a safety.

The newspaper account doesn’t make sense, but that’s how the final score was recorded. An accurate score probably was 13-2.

STRANGER THAN FICTION II

Army-Navy’s Harry DeVenny hit an Oceanside receiver so hard that the Pirates’ receiver fumbled and then punched DeVenny.

Referee Glenn Broderick ejected the Oceanside offender, at which point Pirates coach Bob Carpenter, either upset with the player or referee Broderick, or both, pulled his team from the field.

Two seconds remained in the half.

After much cajoling, Carpenter finally agreed to send out his third and fourth stringers for the second half, which was limited to five minute quarters.

Army-Navy’s scored all of its points in the first quarter of the 17-0 victory, twice on blocked kicks and once on a bad Oceanside snap from center that resulted in a safety.

HOOVER GETS LIGHTS

The Sports Field will be an “Eastern San Diego Community Center,” according to Cardinals principal Floyd Johnson.

Large headline in The Cardinal, weekly official publication of the Herbert Hoover Senior High School, shouted, “Lights Will Blaze on Hoover Field” and “Big Educators Will Congratulate Hoover Only Lighted Field.”

What the second headline meant was that Hoover would be the only school in the County with illumination for football games. And principal and master of ceremonies Johnson had lined up City Schools honchos to mark the occasion.

Speakers at the dedication game with the Riverside Sherman Indian squad would be Dr. Chester Webber, president of the San Diego Board of Education; Will C. Crawford, superintendent of schools, and Jack Ryan, president of Hoover’s previous June graduating class, which contributed $243 to the project.

Hoover’s girl tumblers would entertain at halftime and the 40-member Hoover band would play, with yell leaders and song leaders following their cues.

Hoover won the inaugural game, 26-0.

SCARY BUS RIDE

The bus taking Coronado footballers to their game at Grossmont was moving along El Cajon Avenue when the driver noticed an oncoming car weaving in and out of traffic.

The bus suddenly veered to avoid the car and ran off the road, sheering a telephone pole, and coming to rest near the intersection of College Avenue and El Cajon Avenue.

All passengers were shaken but okay. Grossmont officials then sent a bus for the Islanders.

POSTSEASON NIXED

Grossmont could afford transportation for the Coronado team, but expense apparently was the reason the Foothillers opted not to enter the Southern Section playoffs for the second season in a row.

The Foothillers were undefeated for the second consecutive season but school principal Carl Birdsall believed it cost too much to bus the players to the Los Angeles area for a game.

Birdsall, citing financial concerns, also announced that the 1935 edition of the El Recuerdo yearbook would be eliminated.

The yearbook staff and class advisor raised enough money to ensure the annual’s publication.

Times were tough during the Great Depression.

SIGNS OF THE TIMES

Two burglars, apparently well into the sauce, gained entry to the Fox Theater at Seventh Avenue and B Street, at 2 a.m. and forced the night custodian to take them to the office safe.

John Thompson convinced the inebriated crooks that he didn’t know the safe combination. The pair staggered out of the theater with no money but took an evening dress used by Miss Dixie Barnes, theater hostess.

SWEETWATER GENERATIONS

Lyle and Leon Finnerty were important contributors to Sweetwater’s 6-1-1 record, the Red Devils’ best since 1926.

Lyle was the second-highest scorer in the County with 73 points (San Diego’s Ambrose Schindler had 90) and his son, Jim, was a three-sport star at Sweetwater in 1964, leading the Red Devils to a 6-3 record and passing for 15 touchdowns.

HONORS

San Diego’s Ambrose Schindler was the only first-team, all-Southern California choice. Tackle R.C. Moore of San Diego made second team. End Cozen of Oceanside was on the third team. Hoover nemesis Harry (Biff) McLaughlin of Santa Barbara was on te second team.

TRUE GRID

San Diego was unsuccessful in scheduling a post season game in Nevada against the Las Vegas Wildcats…as writer Nelson Fisher said, “It would give the Hilltoppers a pleasant trip and a chance to see Boulder Dam”…the Cavemen also were unable to get a game with Inglewood, which upset San Diego in the 1933 Southern California finals…San Diego’s itinerary to its game at Phoenix Union: Buses left school at 7 .am., lunch in Yuma, Arizona, arrived in Phoenix at 6 p.m. and practiced at 8…game the next day…proceeds from the Hoover-San Diego Elks Charity Game provided grocery baskets for San Diego families…attendance for the San Diego-Hoover game was 12,000, double the turnout for Santa Ana-San Diego…Army-Navy’s all-Metropolitan League halfback Norm Montapert had been all-City at Los Angeles Belmont in 1933…a pool of 38 officials worked 96 San Diego County games…Grossmont’s Jack Mashin sent prospective members of his 1935 squad to a game with the Green Valley Falls Civilian Conservation Corps team at the end of the season…La Jolla students and town folk wanted to see more of coach Lawrence Carr’s Vikings, who had enjoyed a 6-1-1 season, best in school history…Carr prevailed on San Diego coach Hobbs Adams to bring his junior varsity to La Jolla for a season-ending game…La Jolla won, 34-0….

From Tommy’s 1963 Saints class. Always invited Tom to our reunions. Considered him our brother. Many, many prayers. Charles, or as Tom called me, (Cholly).

Thanks for writing. Tom would be pleased, I’m sure.

Having read this I thought it was really enlightening.

I appreciate you finding the time and effort to

put this information together. I once again find myself spending way too

much time both reading and posting comments.

But so what, it was still worthwhile!

Thanks Rick. That was awesome. Always interesting learning about family history.

Thank you, Dean. I knew both twins. Wayne was my junior high gym coach and Bill was my landlord at one time.