1973: Back to the Future

Sixteen teams, divided by two upper and lower brackets made for the largest postseason in San Diego Section history.

What had gotten into the CIF bosses?

They had repeatedly recited the dubious mantra that the playoffs made the season too long and were a “major” reason for bolting the Southern Section.

To win a Southern Section championship, teams would have to play as many as four playoff games, adding a month to the football season, although San Diego teams seldom played beyond the second round of games.

The most notable result of the San Diego Section’s formation in 1960 was that a champion would be decided in a postseason of two weeks. Four of 21 AA teams, 19 per cent, made the playoffs.

By 1965 only seventeen per cent of 35 AA clubs were in the postseason. One playoff involving two teams decided the Class A winner.

Complaints from coaches, fans, and media grew, as many teams with good records were not invited.

MORE THE MERRIER?

The CIF began to fudge on its original argument. Slowly the number of teams qualifying for the second season began to rise.

The bosses gerrymandered the final week of regular-season schedules in 1966 by having two teams compete in a “play-in” game, the winner going to the postseason, although playoffs remained at two weeks.

The CIF created the unpopular double champions format in 1967. “Metropolitan Conference” and “County Conference” winners were crowned. Nine of the 37 AA schools, 24 per cent, made the playoffs. The postseason still was two weeks.

The two-conference format also was in effect in 1968 and 1969, but a third postseason week matchig the conference winners was added. Escondido, 10-1-1, and San Diego, 8-3-1, tied for the championship, 21-21.

Champions from 1969 forward would play 12 games, the same as San Diego in 1916, ’55, and ’57 Southern California playoff seasons.

(The regular season in most leagues had gone from 8 to 9 games in 1964. The Grossmont League stayed at eight until 1970, the schools in that circuit having played in the game-counting, money-making carnival through 1969).

BREAKTHROUGH THIS YEAR

By 1972 there were 51 football-playing clubs and the postseason included 8 of the 40 AA squads, still just 20 per cent.

The floodgates opened this year.

Sixteen teams, representing 35 per cent of the 43 AA teams went to the postseason. A single contest decided the A champion.

Thirteen games and four weeks to decide a champion? Things were back to the way they were.

CITY SETS PACE

Seedings for the playoffs were done by a coaches’ committee and evoked none of the usual complaints.

The four semifinalists, Kearny, Patrick Henry, Sweetwater, and San Marcos, had a combined record of 38-3-2.

Kearny shut out Sweetwater, 34-0, in one semifinal and then took out Patrick Henry, 35-13, in the finals. It was the first time in eight seasons that Komets coach Birt Slater did not lose in the first round.

A 28-14 victory over Point Loma in the regular season was Slater’s 100th. He became the third, after Jack Mashin and Chick Embrey (see below), to reach that mark.

GROWTH=MORE LEAGUES

The Avocado and Metropolitan leagues were bulging. The Eastern and Western leagues lacked symmetry, thus a new circuit, the AA Coast, was created.

The city’s Eastern and Western leagues now listed six teams each. The Avocado reduced from nine to seven and the Metropolitan from nine to eight. The Grossmont League stayed at eight.

The Coast, with Coronado at the South end and San Dieguito and Poway in the North, would last only three years.

Coronado, buffeted by small enrollment for years in the Metropolitan League, now traveled 30 miles to Poway and 28 miles to San Dieguito and still faced schools with double its number of students.

How the changes went down:

| Team | 1973 League | 1972 League |

| Coronado | Coast | Metropolitan |

| San Diego | Western | Eastern |

| Mission Bay | Coast | Western |

| La Jolla | Coast | Western |

| Poway | Coast | Avocado |

| San Dieguito | Coast | Avocado |

DAY, YEA, NIGHT, NAY

San Diego’s population had risen from 573,000 in the 1960 census to about 735,000. The County total was almost 1.4 million. Twenty-one schools not part of the original San Diego Section football lineup were now in business.

The growth strengthened the CIF, but the bosses were having a difficult time getting their hands around a spike in rowdyism and violence at game sites.

Stop and frisk wasn‘t part of the solution, but, following the lead of other major cities, an unpopular decision was made.

“Night football and basketball games in the San Diego City School District will end with this season’s athletic schedules, school officials announced yesterday,” wrote The San Diego Union education writer Ray Kipp.

The vote of 4-1 gave school district superintendent Tom Goodman authority to schedule night athletic events to afternoon competition, wrote Kipp.

The reason was violence.

A specious argument was that the “growing unavailability of fields” and a desire to “conserve energy” influenced the board’s action .

(The long waits and gasoline shortage that hounded Americans in 1973 would be ended when the oil-rich middle east countries lifted a ban on oil exportation to the U.S. in March, 1974).

The night-games ban came despite protests by students and adults who opposed any change without in-depth studies and potential effects on school spirit, game revenues, and the opportunity to attend afternoon contests.

In response, tone-deaf school board member Louie Dyer said, “If people really want to go to an afternoon game, they will.”

Board member Richard Johnston voted against the measure, citing the punishment that would be inflicted on students by the action of non-students.

Only one of 12 speakers appearing before the board voiced support for the change.

PAOPAO AS IN POW!

Anthony Paopao would have been welcome in the company of Frank Gansz’ special teams players on the Super Bowl 34-champion St. Louis Rams of 1999.

Paopao embodied the espirit and toughness that Gansz, a Naval Academy graduate and pilot, rewarded on Mondays following games in that memorable season.

Make a play, show toughness and desire, and a deserving Rams player would receive a baseball cap inscribed “Warrior Elite”.

It was ultimate praise and those recognized wore the headwear with pride.

Gansz would have been a PaoPao fan.

Oceanside coach Herb Meyer continually called PaoPao’s number in the playoffs against Mission Bay and the 190-pound junior responded again and again on the soggy, rain-dampened Simcox Field.

PaoPao touched the ball on 68 percent of the Pirates’ offensive plays, scored from 18 and 15 yards, including the come-from-behind, 13-10 game winner in the fourth quarter, and rushed for 213 yards in 41 carries.

BUCCANEERS REVIVED The playoff loss was disappointing but didn’t dim a gratifying year for Mission Bay.

Three seasons and a 2-25 record that included 18 losses in a row were staring at coach Al Lewis when practice began at the Pacific Beach school in September.

Lewis, who started the football program at Point Loma’s Cal Western University in 1957, had succeeded Bill Hall at the Grand Avenue location in 1970.

It helped that the Buccaneers moved this year from the Western to the less competitive Coast League.

A 7-2 regular-season record tied the 1958 squad for the most successful in school history and earned the Bucs the first Coast League championship and their first playoff invitation since they first teed up in the 1954 inaugural varsity season.

Lewis was 31-50-2 overall but 29-25-2 from 1973 until he stepped down after the 1978 season.

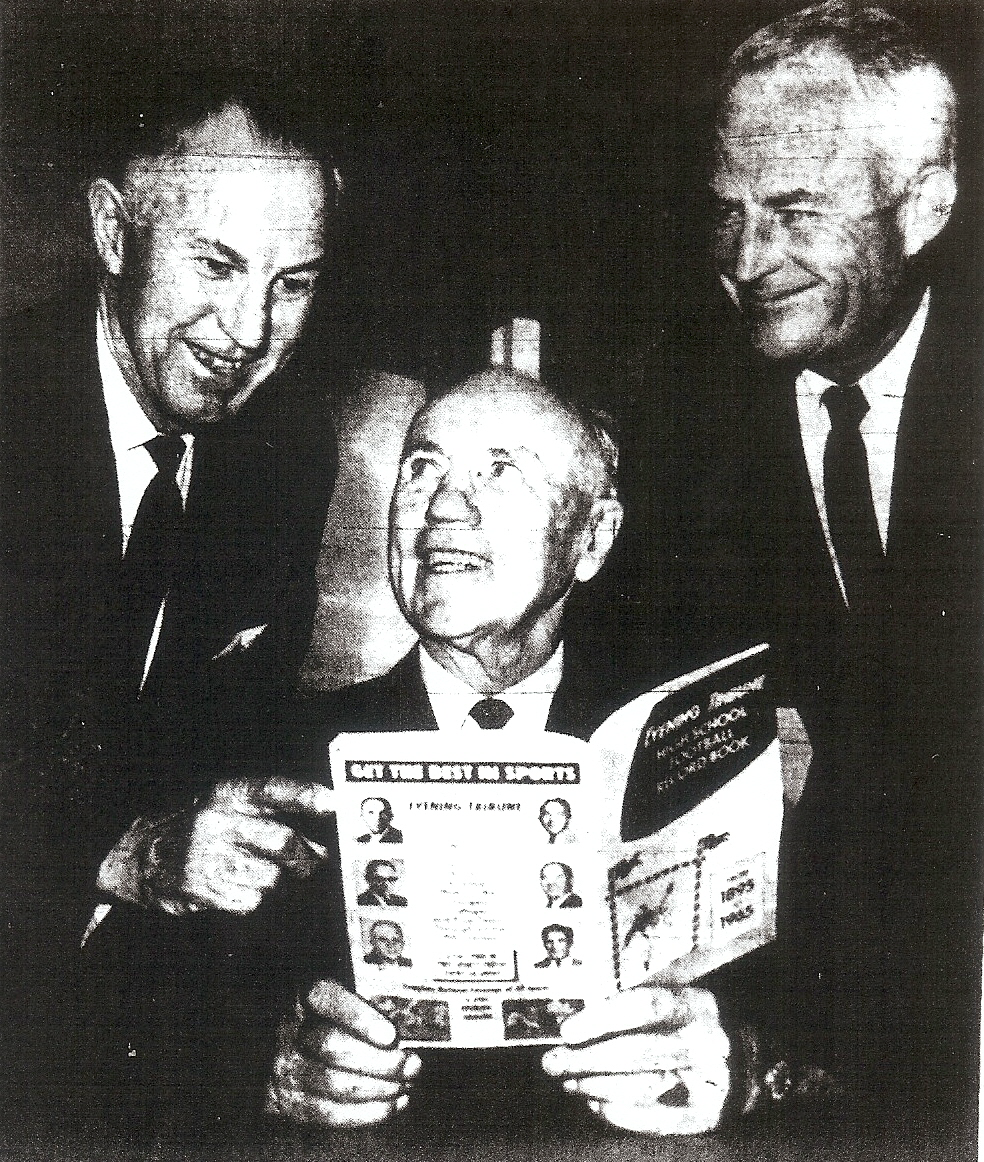

EMBREY TIES MASHIN

Ladimir (Jack) Mashin, who coached at Grossmont from 1923-47, had held the County record for most coaching victories since he retired after the 10-1 campaign of 1947.

Mashin was 121-65-15 (.639) and figured at the start of this season to be caught by Escondido’s Chick Embrey, who had fashioned a 118-45-4 record since becoming head coach in 1956.

Embrey didn‘t catch Mashin until the Cougars’ eighth game and passed him in the final game of a 3-6 disappointment by defeating Fallbrook, 23-6.

Mashin, 75, whose record was later amended to 125-66-19 (.640), still was active, assisting the weight men (shot put, discus) on the Grossmont College track team. He expounded on the modern game.

“There are 4-4-2-1 and 4-5-2 defenses and you get stunting and all that which you never had when I was coaching.” Mashin told Will Watson of The Union.

“I wish I was coaching under the present system, where you could see games on TV. If I were a coach today I’d be glued to the TV.

“Of course,” Mashin added, “in my day there was no TV, so we tried to go to as many coaching clinics as we could.”

PERRY SUCCUMBS

John Perry, the 78-year-old former coach at San Diego and Hoover, died Oct. 21 from injuries sustained in an auto accident on Sept. 10 near his retirement home on San Diego’s Bankers Hill.

Perry, who never played football, learned the game by reading football books and printed pamphlets, and traveling hundreds of miles to attend clinics.

Perry coached at San Diego from 1920-26, winning a Southern California title in 1922 and earning a trip to the finals in 1925.

Perry left coaching but returned and built the Hoover program from scratch in 1930 and led the Cardinals to their first victory over San Diego in 1935.

“He was a great coach and a great personal friend,” Bert Ritchey, the star of the 1925 squad, told Bill Center of The Union. “We all knew he never played, but he was one man with no playing experience who could teach it.”

“He wasn’t only a coach, he was like a father to us,” said Roy Engle, who scored the touchdown in Hoover’s 7-6, first win over the Cavemen . “It was John who turned my eyes to a coaching career.”

Perry was 52-14-5 at San Diego and 40-34-6 from 1930-39 at Hoover.

MIKE MORROW, TOO

The San Diego sports world was saddened again seven weeks later when Dewey J. (Mike) Morrow the nationally renowned San Diego high coach and peer of John Perry, passed away at 75.

Morrow coached 10 Southern California baseball championship teams and the only San Diego County team to win a Southern California major division championship in basketball, in 1935-36.

QB AS SPORTS WRITER

Kearny junior Don Norcross, who led the County with 1,270 passing yards, was destined for a career as a sports staff ace for the Union-Tribune.

Norcross entered the season as the only question mark on a loaded Kearny squad. “Sure, I felt the pressure,” he said. “It was like, ’If Kearny doesn’t make it, it will be Norcross’ fault.’”

SHORT BUT NOT SMALL

Player-of-the-year Ed Imo was the 5-foot-9, 230-pound line-plugging nose tackle for the Komets’ defense.

Imo went on to star at San Diego State and later became the physical education/athletics department chairman in American Samoa,

“Had I played against him, I would have spent a lot of time face-first into the grass,” said Norcross.

Ed Imo had another distinction at San Diego State, the shortest name in Division I football, five letters.

RED DEVILS BEDEVILED

Sweetwater’s 27-game Metro League winning streak, which began in 1969 after a 41-0 loss to Castle Park, ended in a 12-8 loss to the Trojans.

AND BEYOND

Future NFL standouts included St. Augustine wide receiver Tim Smith, Kearny defensive back Lucious Smith, Castle Park defensive back John Fox, who became an NFL head coach; El Cajon Valley quarterback Mark Malone, and Hoover defensive lineman Bill Gay.

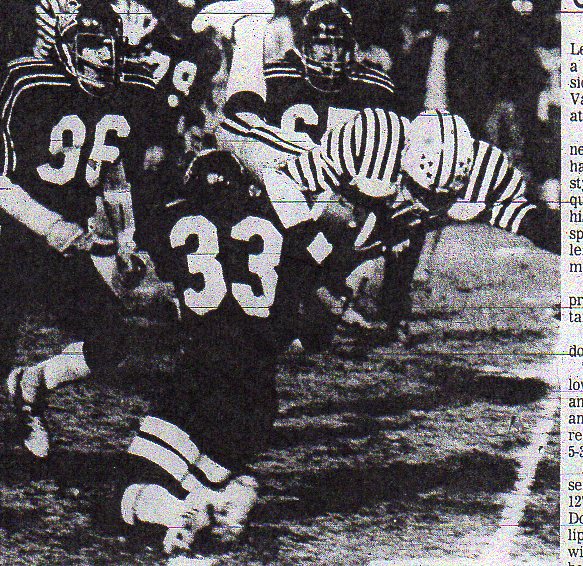

San Diego’s Michael Hayes, who led the County with 1,418 yards rushing, including 858 in his last four games, did not play in the NFL but was one of the all-time great San Diego running backs.

Hayes was just warming up. He’d be the San Diego Section player of the year in 1974 and was named to the second all-time, all-County team in 2013.

CAVEMEN COLLAPSE

Hayes was a one-man show against Point Loma, scoring three touchdowns and gaining 223 yards in 28 carries, but his team offered no defense against Point Loma.

The Pointers’ 54-28 victory over San Diego represented the most points allowed by the Cavemen since a 56-0 loss to the Stanford University freshmen in 1923. Point Loma’s John Finley scored four touchdowns and gained 123 yards in 22 attempts.

QUICK KICKS

.Hoover coach Roy Engle had to devise a defense for the Crawford quarterback, the position played by his son, David…Carlsbad snapped an 0-6-1 stretch against Oceanside, 17-8…Lincoln did not kick a point after touchdown or field goal all season……Bill Casper, Jr., son of the former U.S. Open golf champion Billy Casper, was a star lineman for Hilltop….