1917: Hilltoppers Learn it’s Difficult to Repeat

Uneasy rested the crown.

San Diego High, anointed the best high school team in the country by a New York publication after the 12-0 campaign of 1916, experienced a season of highs and lows, emphasis on the latter.

Coach Clarence (Nibs) Price, who started practice in September with news that his best player was “dangerously ill with fever”, missed a playoff game that was coached by one of his players, and the Hilltoppers ended the season with a 0-55 thud.

Karl Deeds, an integral part of the championship squad who was forced to drop out of school to work and then was reinstated, mentored a 28-0 victory over El Centro Central from the City Stadium sideline as Price was away in Los Angeles, attempting to join the aviation corps.

The Great War in Europe had a far-reaching effect.

MULLER BACK

The “dangerously ill” Brick Muller recovered from fever and was back in uniform about three weeks into practice, but his was an uneven season.

Muller sustained a broken collarbone against the Occidental University frosh, missed rivalry games versus Long Beach Poly and Santa Ana, and was in and out of action for the remainder of the year.

Muller was a star end on the 1916 squad, making all-Southern California, and was the centerpiece of what Price hoped would be another championship entry.

The player was held in such high regard on campus that Muller was elected to the school’s athletic “executive committee” for the second year in a row, while he was home sick in bed.

FAREWELL

Price was back at his post and on the field for the season and tenure-ending, 55-0 playoff semifinals loss to Los Angeles Manual Arts, which the Hilltoppers defeated for the 1916 championship.

Baseball would provide a valedictory for Price, who left the school at the end of the spring semester, as the Hilltoppers overcame a 5-5 start, won seven of their last eight games and claimed Southern California and state titles.

The diminutive (5 feet, 6 inches) mentor entered the military and then returned to alma mater University of California, where he was appointed assistant football coach in 1919 and began a legendary career in Berkeley.

Price became head basketball coach in 1924 and held that position for 30 years. He also served in the rare, dual role as football and basketball head coach from 1926-30.

Price’s basketball teams won more than 453 games and his 1944-45 club reached the national collegiate Final Four, posting a 30-6 record. The 17-0 squad of 1926-27 was named national champion by one publication.

MULLER ALSO LEAVES

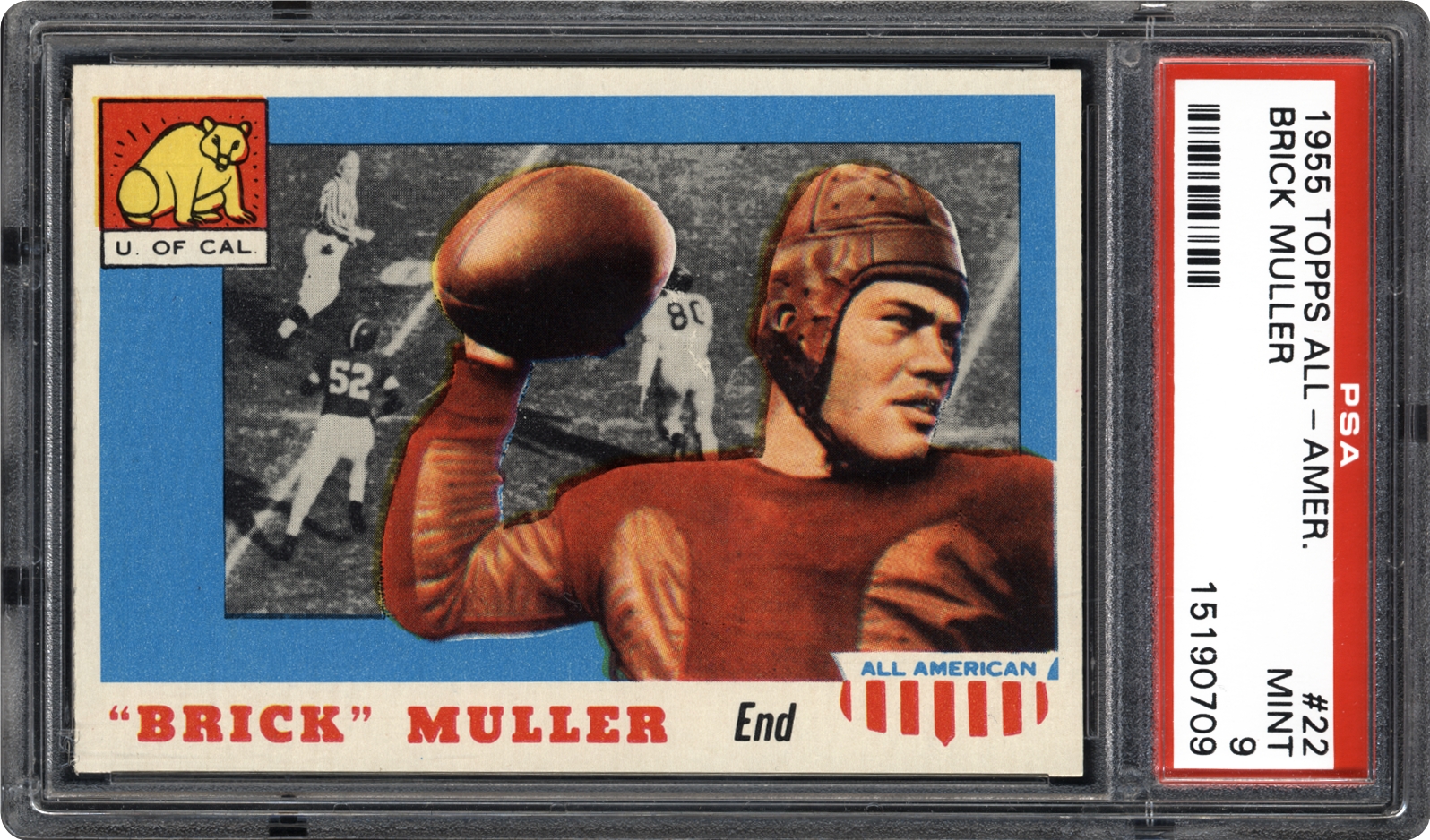

Price occupies a significant position in Hilltoppers lore, but Muller became an athlete for the ages.

Muller beat Price to the door, transferring to Oakland Technical in the Bay Area in the spring and eventually joined the coach in Berkeley, along with six of Muller’s 1916 teammates.

While playing rugby, the sport of choice at Oakland High in 1918, Muller sustained a broken jaw. He still hooked up with the former San Diego High footballers by occasionally practicing with the University of California squad.

Muller won the state prep high jump championship in 1918 (5-11 ½) and 1919 (5-6) and was a silver medalist in the 1920 Olympics at Antwerp, Belgium, with a leap of 6-2 ¾.

The first Western player to earn all-America football honors, in 1921 and 1922, Muller threw the longest pass in Rose Bowl history (reportedly 57 yards in the air, with the vintage, oblong ball), and was a point producer in track, finishing second in the broad jump, third in the high jump, and fourth in the discus at the IC4A championships.

The venerable Intercollegiate Association of Amateur Athletics of America, founded in 1879, was a predecessor to today’s National Collegiate Athletic Association.

Muller became an orthopedic surgeon and was team physician for years at California. A little known fact, he likely was the first NFL player from San Diego.

Muller joined the one-season Los Angeles entry in 1926 and became the team’s coach later in a season in which the Buccaneers played all of their league games on the road, with headquarters in Chicago and players from California colleges.

IN OR OUT?

San Diego competed as an independent. It was invited to join the Los Angeles County League. Or was it?

Price and principal Arthur Gould attended a Los Angeles meeting and returned home saying the Hilltoppers would join, replacing Whittier, which dropped out, saying its team was “too light.”

Pasadena, Long Beach Poly, and Santa Ana were other members.

A few weeks later bosses at Whittier announced they wanted back in. Pasadena, saying San Diego never was a member, voted for Whittier.

The issue seemed nebulous, just another in what would be almost annual issues involving the distant Hilltoppers and what to do with them.

PLAYOFFS ANOTHER ISSUE

San Diego’s 14-game winning streak was snapped by Hollywood, 27-10, and the Hilltoppers were dropped from the postseason after a second loss, 27-3 to Long Beach.

Price and Gould traipsed to Los Angeles again, complaining to CIF manager Harry J. Moore that they had not been notified of the playoff meeting at which they were eighty-sixed.

Gould also reminded Moore that San Diego was the defending champion and that the Border City squad was in possession of the CIF championship cup.

Gould’s oblique reference to the bauble and its location seemed to have a desired affect.

CIF signals quickly were changed. San Diego was slotted against Coronado, the County League titlist, for the right to meet El Centro Central in the playoff quarterfinals.

Coronado scored for the first time in three games against San Diego and led the Hilltoppers, 13-7, before bowing, 14-13.

The San Diego-Coronado contest, played before about 500 persons, would be very unique in later years. The game consisted of four, 13 1/2-minute quarters.

SHORTER SEASON?

“I do not expect to play twelve games this year, six or possibility seven,” Price told a local writer before the first practice.

“Last year the strain was entirely too hard on the players and I would not care to take a team through such a late season as that of last year, which lasted until late December,” said Price.

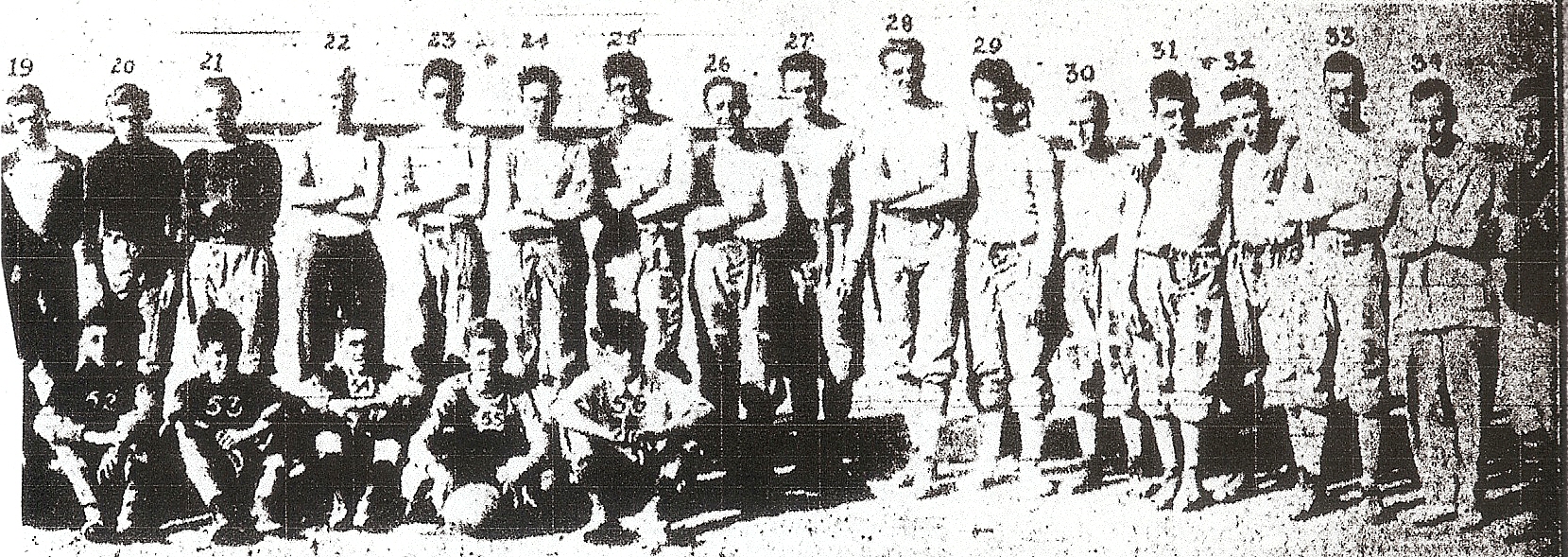

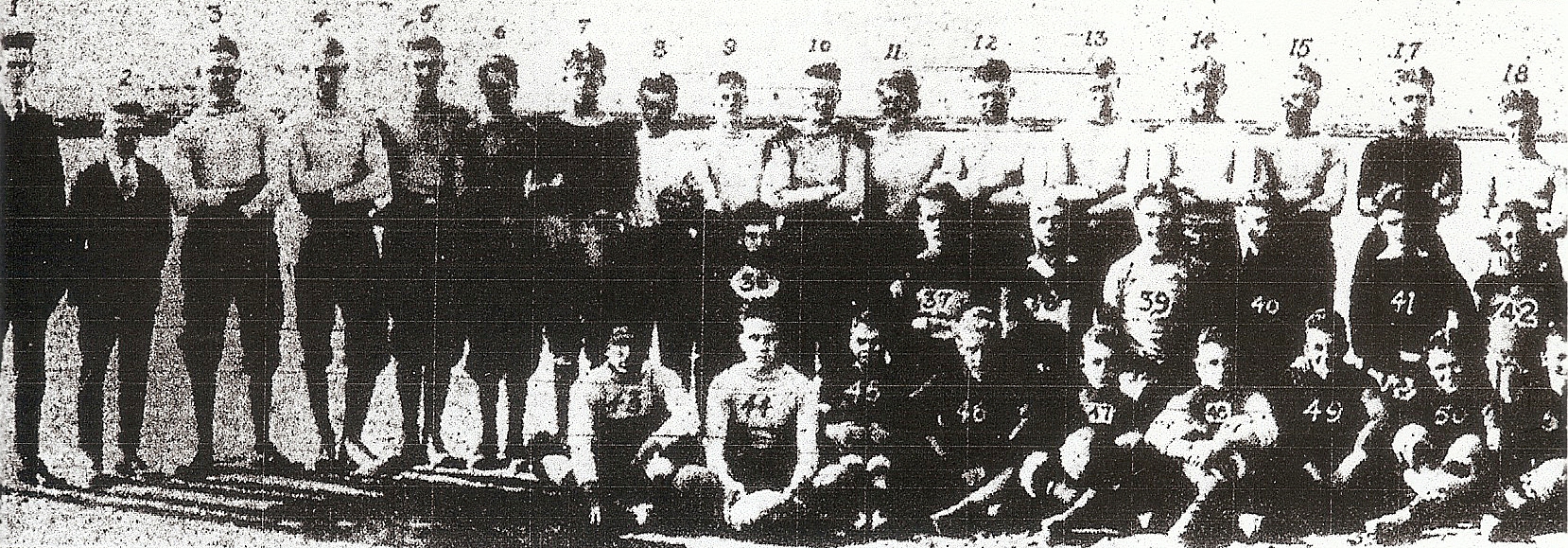

With Del Beekley, an energetic student manager, daily contacting schools throughout Southern California in an attempt to book games, the Hilltoppers played 11 and posted a 5-4-2 record.

Media accounts never made clear how much say Price had regarding the number of games played or opponents and whether the decisions were made by student managers, who were involved in all aspects of the program except coaching.

Published accounts on scheduling usually referred to the efforts of the student manager, although the head coach and the school principal attended CIF and league meetings, which were held in the Los Angeles area.

PRICE NIXED ’16 STATE GAME

It was Price who made the decision to pass on Bakersfield’s challenge to a state championship contest in 1916.

There was some fallout with the claim from the Kern County school that the Hilltoppers forfeited the title to Bakersfield, but that was specious.

San Diego was not compelled to play another game after its Southern California championship.

Price gained vindication of a sort when San Diego defeated the visiting Bakersfield Drillers, 18-7, on Thanksgiving Day.

MARKETEER BEEKLEY

The diminutive Beekley, who decades later was crew coach at San Diego State and was a founder of the San Diego Crew Classic in the 1970s, created one marketing promotion after another.

Students selling the most tickets to the Bakersfield game, which represented the first half of a doubleheader also featuring local service teams, would be given a number of free passes.

Four additional prizes would be awarded to students who created the most artistic, game-related poster illustration.

The prizes included a silver loving cup, two, 4-pound boxes of candies, one, 1-pound box of candies, and a box of stationary from Eastman-Kodak.

BANTAM-SIZED GIANT

Beekley, who stood 5 feet tall, passed in 2001 at age 102 after spending 77 years in or around a rowing shell, first as coxswain for San Diego Rowing club.

Beekley sought a New Year’s Day extravaganza for the Hilltoppers. He said he had Price’s support (despite’s Price’s earlier stated desire to shorten the season) for a game with Arizona champion Phoenix Union.

“…I intend to take the matter before the student body executive committee to see if they will not grant permission for such a game,” Beekley said.

The manager made his remarks to a reporter from The San Diego Union. A decision was made, by the student executive committee, principal Charles Gould, or Price, not to extend the season.

HUGE MILITARY EFFORT

Thousands of soldiers were in training at nearby Camp Kearny, where the government announced that 14 miles of roads, would be constructed in three weeks to meet the needs of the U.S. Army.

Camp Kearny had quickly risen on almost 13,000 acres of land that is known today as the site of the Marine Corps Naval Air Station.

The camp, named after a 19th century officer and the mesa on which the land was located, was extant from 1917-46, operated first by the army, which turned the base over to the navy in 1932.

Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny served as California’s military governor before statehood in 1847 and has been called the father of the cavalry.

SIGNS OF THE TIME

The new military facility officially was Camp Kearny, after some disagreement on its spelling.

Contractor William E. Hampton had asked San Diego postmaster L.R. Barrow for clarification. Barrow said, “Kearney,” but was overruled.

Adjutant general P.C. Harris officially ordered the name “Kearny” on July 18, 1917.

There was no mention of Stephen Kearny in the adjutant general’s document.

(for more on Kearny, search: “1944: The Temporary Suburbs”).

HIT THE ROAD

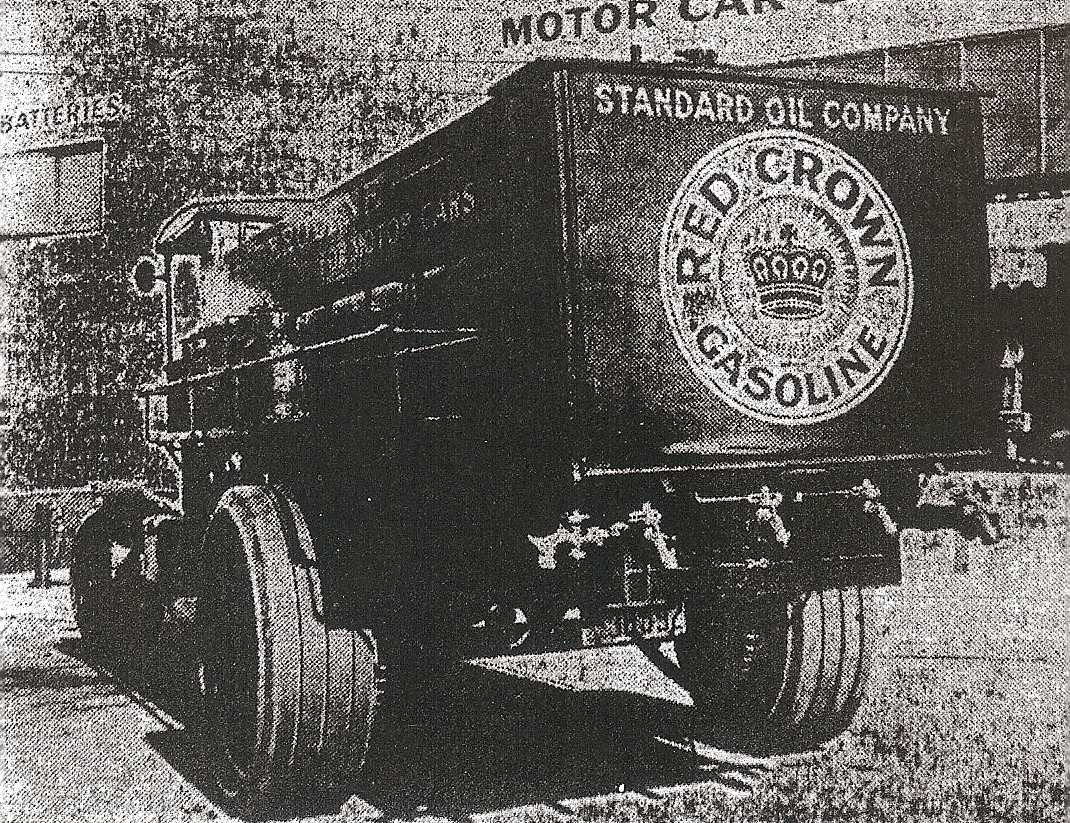

Standard Oil of California heralded one of its San Diego-based vehicles as being equipped with “the largest tire ever seen on the Pacific Coast.” The mass of rubber weighed 500 pounds, was 14 inches wide, and 42 inches high.

ANTI-BOOZE

Evangelist Billy Sunday spoke of the evil of Demon Rum when he addressed the City Stadium gathering before the Hilltoppers played Pomona.

Prohibition did not go into effect until 1920.

Manager Beekley had tags printed that allowed all who came to hear Sunday to stay for the game.

Sunday’s appearance apparently boosted the attendance. The Hilltoppers announced a gate profit of $110.

ILLUMINATION

With no lights in the stadium and the sun fading fast in December, Hilltoppers coach Nibs Price introduced a silver football for practice, which started later and lasted longer, according to the Union.

“ELEVATOR, ELEVATOR…

…we got the shaft!”

That was the feeling of the National City (Sweetwater) varsity when play was suspended after what passed for trash talk of the era escalated into a fist-swinging free-for-all with the San Diego Seconds team.

Sweetwater, which lost an earlier game to the Hilltoppers Seconds, 18-0, and was trailing, 12-0, when fighting broke out, accused San Diego of using “illegal tactics”.

The two officials were connected to the big city school downtown.

Brick Muller was the umpire when San Diego had the ball. Bill (Bull) Salyers, 1915 team captain, was umpire when Sweetwater was in possession.

QUICK KICKS

Reginald Sidney Gurling of La Mesa was the first San Diego soldier killed in the war…Ralph Noisat, student manager in 1916, quit his job at a local bank to take a position in the playground department, beginning at Golden Hill playground with Lee Waymire, who later was head coach at Coronado…Sammy Sampson, Walter (Dutch) Eels, and Clyde Randall, recent graduates and players on the 1916 squad, assisted Price during early practices, which accentuated “falling on the ball (fumble recoveries) and “learning how to pass”…Paul (Rat) Hyde, the Hilltoppers’ quarterback in 1910, also was a sideline observer…so determined to avenge the championship loss of a year earlier, Manual Arts students lined school corridors with signs that said, “San Diego or Bust”…principal Arthur Gould suggested that all Hilltop athletes wear corduroy trousers to school…about 35 complied…winning the County League championship had currency in Coronado…the Islanders were honored at a school dance and would be guests of honor at 4 upcoming dinners…local media referred to the visiting Santa Ana Saints as the “celery growers.”…the Saints’ 12-0 victory was “for the championship of Orange and San Diego counties”…four quarters of 15 minutes was not the norm…many games were played to a convenience of time…San Diego’s 27-0 victory over Los Angeles Poly was achieved with 12-minute, 30-seconds quarters…playoff opponent El Centro Central came into the game with a 4-1 record, their five games against the only other schools in the Imperial Valley that played football, Calexico (1-1) and Holtville (3-0)….